Oxford, Jonson and the Crisis of Aristocratic Merit

Oxford, Jonson and the Humanist Critique of Aristocratic

Worth

Renouncing Exemplarity

Oxford – Exemplary

homme a la mode

Sociability and Worldliness in the Elizabethan Court

Mocking Courtly Sociability in Cynthia’s Revels

Le Monde/The Globe

***************************************

Admirable Oxford or Graceful Trifler? Pergraecari

At this point in time I'll suggest that Oxford resisted the exemplary models of his classically-trained humanist educators (imitation) and instead charted a more individualistic path of aristocratic sociability and aesthetic excellence (invention). The resultant figure of the refined and cultivated man-of-the-world appears to have set off a bit of a craze among aspirational gentlemen in England. However, based in part on an Italianate model, the figure of the perfect courtier or cavalier (addressed to all men of good will; witty and somewhat cheeky) was not entirely well received in England. The most scathing critiques of Oxford's person and his art suggested that he had cobbled himself together in a monstrous fashion out of the rags and shreds of other men and other cultures and forms. At the time of his death he was considered not to be an exemplary figure according to the political and educational biases of the times. His checkered reputation and his literary legacy (Shakespear's Works) have descended to us along separate lines - with spectacularly different results.

****************************************

****************************************

Admirable Oxford or Graceful Trifler? Pergraecari

At this point in time I'll suggest that Oxford resisted the exemplary models of his classically-trained humanist educators (imitation) and instead charted a more individualistic path of aristocratic sociability and aesthetic excellence (invention). The resultant figure of the refined and cultivated man-of-the-world appears to have set off a bit of a craze among aspirational gentlemen in England. However, based in part on an Italianate model, the figure of the perfect courtier or cavalier (addressed to all men of good will; witty and somewhat cheeky) was not entirely well received in England. The most scathing critiques of Oxford's person and his art suggested that he had cobbled himself together in a monstrous fashion out of the rags and shreds of other men and other cultures and forms. At the time of his death he was considered not to be an exemplary figure according to the political and educational biases of the times. His checkered reputation and his literary legacy (Shakespear's Works) have descended to us along separate lines - with spectacularly different results.

****************************************

Arthur Golding to Edward de Vere (Epistle Dedicatorie,

Psalms):

...I beseech your Lordship consider how God hath placed you upon a high stage in the eyes of all men, as a guide, patterne, insample and leader unto others. If your vertues be uncounterfayted, if your religion should be sound and pure, if your doings be according to true godlines: you shal be a stay to your cuntrie, a comforte too good men, a bridle to evil men, a joy to your friends, a corzie to your enemies, and an encreace of honor to your owne house. But if you should become eyther a counterfayt Protestant, or a perverse Papist, or a colde and careless newter (which God forbid) the harme could not be expressed which you should do to your native Cuntrie. For (as Cicero no lesse truely than wisely affirmeth and as the sorowfull dooings of our present dayes do too much certeinly avouch) greate men hurt not the common weale so much by beeing evil in respect of themselves, as by drawing others unto evel by their evil example...

...I beseech your Lordship consider how God hath placed you upon a high stage in the eyes of all men, as a guide, patterne, insample and leader unto others. If your vertues be uncounterfayted, if your religion should be sound and pure, if your doings be according to true godlines: you shal be a stay to your cuntrie, a comforte too good men, a bridle to evil men, a joy to your friends, a corzie to your enemies, and an encreace of honor to your owne house. But if you should become eyther a counterfayt Protestant, or a perverse Papist, or a colde and careless newter (which God forbid) the harme could not be expressed which you should do to your native Cuntrie. For (as Cicero no lesse truely than wisely affirmeth and as the sorowfull dooings of our present dayes do too much certeinly avouch) greate men hurt not the common weale so much by beeing evil in respect of themselves, as by drawing others unto evel by their evil example...

****************************************

Framing Authority: Sayings, Self, and Society in

Sixteenth-Century England

By Mary Thomas Crane

…[It] was a deeply threatening idea that a particular kind

of education (or, indeed, a prose style indicative of that education) could

replace birth and wealth as criteria for access to power. It posed the greatest

threat, as Lawrence Stone points out, to the aristocrats whom it disenfranchised,

and until they were able, in the seventeenth century, to recast educational

credentials on the basis of attendance at certain elite (and expensive)

schools, they were forced to reassert an alternative training for aristocratic

youth. It also threatened the humanists themselves, who saw in their own upward

mobility not only potentially dangerous eminence but also a disquieting

acquiescence in capitalist and republican tendencies and a palpable threat to

the concepts of order and hierarchy that they promulgated. These issues surface

(in the 1520s through the 1540s) in the form of preoccupation with “value,” and

in discussions of what society ought to value and how “wealth” (both monetary

and cultural) should be displayed and shared.

Stone has shown how

the “educational revolution” effected by English humanists contributed to the

“crisis of the aristocracy” in the seventeenth century. He argues that in the

sixteenth century, the new ideal of “gentleman” based on education “increased

the opportunities of the gentry to compete for office on more equal terms with

the nobility.” There are signs, however, of ARISTOCRATIC RESISTANCE to the

humanist model of counsel, and in this resistance lie the seeds of the

alternative model of courtly advancement, the ITALIANATE COURTIER. According to

this model, “WORTH” is manifested through the conspicuous consumption of

“worthless” TRIFLES (clothes, jewelry) and participation in frivolous pastimes

(hunting, dicing, dancing, composing love lyrics).

************************************************

Wit as 'Natural', Learning as 'Artificial':

Wit as 'Natural', Learning as 'Artificial':

THE ITALIANATE

COURTIER – THE MIRROR OF TUSCANISM. SINGULARITY and INDIVIDUALISM BEFORE THE COPYING OF EXEMPLARY FIGURES.

******************************************

Steven May, The Elizabethan Courtier Poets:

...Although Dyer has been considered the premier Elizabethan

courtier poet, that is, the first to compose love lyrics there, the available

evidence confers this distinction upon the earl of Oxford. His early datable

work conforms, nevertheless, to one of the established functions for poetry

practiced by Ascham and Wilson. IN 1572, Oxford turned out commendatory verses

for a translation of Cardano's _Comfort_, published in 1573 by his gentleman

pensioner friend, Thomas Bedingfield. This poem differs from earlier efforts of

the kind not so much because it appeared in English (as had Ascham's verses for

Blundeville's book), but because his verses are so self-consciously poetic. The

earl uses twenty-six lines to develop his formulaic exempla: Bedingfield's good

efforts are enjoyed by others just as laborers, masons, bees, and so forth also

work for the profit of others. Oxford flaunts a COPIOUS rhetoric in this poem

in contrast with the more direct, unembellished commendatory verses of his

predecessors. His greatest innovation, however, lies in his application of the

same qualities of style to the eight poems assigned to him in the 1576 Paradise

of Dainty Devices, pieces that Oxford must have composed before 1575.

DeVere's eight poems in the _Paradise_ create a dramatic break with everything known to have been written at the Elizabethan court at that time...The diversity of Oxford's subjects, including his varied analyses of the lover's state, were practically as unknown to contemporary out-of -court writer as they were to courtiers.

Oxford's birth and social standing at court in the 1570's made him a model of aristocratic behaviour. He was, for instance, accused of introducing Italian gloves and other such fripperies at court; his example would have lent respectability even to so trivial a pursuit as the writing of love poetry. Thus, while it is possible that Dyer was writing poetry as early as the 1560's, his earliest datable verse, the complaint sung to the queen at Woodstock in 1575, may itself have been inspired by Oxford's work in the same vein. Dyer's first six poems in Part II are the ones he is most likely to have composed before his association with Philip Sidney. ...Yet even if all six (of Dyer's poems) were written by 1575, Oxford would still emerge as the chief innovator due to the range of his subject matter and the variety of its execution. ...By contrast, Dyer was a specialist...Dyer's output represents a great departure from courtier verse of the 1560's, and several of his poems were more widely circulated and imitated than any of Oxford's; still, the latter's experimentation provided a much broader foundation for the development of lyric poetry at court. (pp. 52-54)

DeVere's eight poems in the _Paradise_ create a dramatic break with everything known to have been written at the Elizabethan court at that time...The diversity of Oxford's subjects, including his varied analyses of the lover's state, were practically as unknown to contemporary out-of -court writer as they were to courtiers.

Oxford's birth and social standing at court in the 1570's made him a model of aristocratic behaviour. He was, for instance, accused of introducing Italian gloves and other such fripperies at court; his example would have lent respectability even to so trivial a pursuit as the writing of love poetry. Thus, while it is possible that Dyer was writing poetry as early as the 1560's, his earliest datable verse, the complaint sung to the queen at Woodstock in 1575, may itself have been inspired by Oxford's work in the same vein. Dyer's first six poems in Part II are the ones he is most likely to have composed before his association with Philip Sidney. ...Yet even if all six (of Dyer's poems) were written by 1575, Oxford would still emerge as the chief innovator due to the range of his subject matter and the variety of its execution. ...By contrast, Dyer was a specialist...Dyer's output represents a great departure from courtier verse of the 1560's, and several of his poems were more widely circulated and imitated than any of Oxford's; still, the latter's experimentation provided a much broader foundation for the development of lyric poetry at court. (pp. 52-54)

**********************************************

Mary Thomas Crane (con't.)

...[A]ristocratic households centered on instruction in music, service at table, and hunting. Of these activities, hunting is most often used to represent this curriculum in contrast to the humanist program. As a famous remark related by Richard Pace in his De fructu qui ex doctrina percipitur (The benefit of a liberal education) sets up the paradigmatic conflict between study and hunting. Pace tells how a drunken nobleman claims that it is more suitable for “sons of the nobility…to blow the horn properly, hunt like experts what Frank Whigham calls the “fetish of recreation”: noble men indulged their preoccupation with sport in order to demonstrate a “mode of life characterized by leisure, spontaneity, the private, the casual.” Only artistocrats, and train and carry a hawk gracefully” than to go noted in previous chapters, the traditional youthful training for aristocrats in prehumanist times took place in to school. Hunting represents training in martial skills necessary to noblemen under the older feudal system and also, increasingly, participates in possessed the status and wealth that enabled development of skill in “trifling” pastimes. Aristocratic training also valued natural grace and ability more than the diligent labor necessary in the humanist classroom. Thus, educated aristocrats are often described as cultus (“cultivated,” implying the cultivation of natural talents) and educated humanists as doctus (“learned,” implying exposure to a given curriculum). (pp., 100-101).

**********************************************

Gabriel Harvey to Oxford:

I have seen many Latin verses of thine, yea,

even more English verses are extant;

thou hast drunk deep draughts not only of the Muses of France and Italy,

but hast learned the manners of many men, and the arts of foreign countries.

It was not for nothing that Sturmius , 2 himself was visited by thee;

neither in France, Italy, nor Germany are any such cultivated and polished men.

O thou hero worthy of renown, throw away the insignificant pen, throw away bloodless books, and writings that serve no useful purpose; now must the sword be brought into play,

now is the time for thee to sharpen the spear and to handle great engines of war.

************************************

Shakespeare:

How careful was I when I took my way,

Each trifle under truest bars to thrust,

That to my use it might unused stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust!

But thou, to whom my jewels trifles are,

Most worthy comfort, now my greatest grief,

Thou best of dearest, and mine only care,

Art left the prey of every vulgar thief.

Thee have I not locked up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art,

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part;

And even thence thou wilt be stol'n I fear,

For truth proves thievish for a prize so dear.

Each trifle under truest bars to thrust,

That to my use it might unused stay

From hands of falsehood, in sure wards of trust!

But thou, to whom my jewels trifles are,

Most worthy comfort, now my greatest grief,

Thou best of dearest, and mine only care,

Art left the prey of every vulgar thief.

Thee have I not locked up in any chest,

Save where thou art not, though I feel thou art,

Within the gentle closure of my breast,

From whence at pleasure thou mayst come and part;

And even thence thou wilt be stol'n I fear,

For truth proves thievish for a prize so dear.

O! lest the world should task you to recite

What merit lived in me, that you should love

After my death,--dear love, forget me quite,

For you in me can nothing worthy prove.

Unless you would devise some virtuous lie,

To do more for me than mine own desert,

And hang more praise upon deceased I

Than niggard truth would willingly impart:

O! lest your true love may seem false in this

That you for love speak well of me untrue,

My name be buried where my body is,

And live no more to shame nor me nor you.

For I am shamed by that which I bring forth,

And so should you, to love things nothing worth.

What merit lived in me, that you should love

After my death,--dear love, forget me quite,

For you in me can nothing worthy prove.

Unless you would devise some virtuous lie,

To do more for me than mine own desert,

And hang more praise upon deceased I

Than niggard truth would willingly impart:

O! lest your true love may seem false in this

That you for love speak well of me untrue,

My name be buried where my body is,

And live no more to shame nor me nor you.

For I am shamed by that which I bring forth,

And so should you, to love things nothing worth.

**************************************

In Cynthia’s Revels Jonson describes Amorphus, the

Deformed as the discoverer of the Fountain of Self-Love. In the 1616 Folio he

identified Amorphus as Edward de Vere by having Amorphus repeat a line of

poetry that had originally appeared in a flattering encomium written to the

earl. It may seem unusual that Jonson resorted to a poem that was decades old

by the time he wrote Cynthia’s Revels, but the choice was apt and serviceable

for Jonson's uses. The line had already enjoyed some infamy having been selected

as an example of vicious speech by Puttenham in his Art of Poetry. In ventriloquizing Southern’s poem Jonson not

only suggests Amorphus’s susceptibility to flattery but also his ‘deformed’

judgement and discretion. Selected by Puttenham as an example of the vicious

‘mingle-mangle’ or soraismus, the line reflects Jonson's apparent opinion that far from being a 'beau esprit', Oxford possessed a ‘deformed’ wit.

****************************************

E P I G R A M S .

Jonson

LVI. — ON POET-APE.

Poor POET-APE, that would be thought our chief,

Whose works are e'en the frippery of wit,

From brokage is become so bold a thief,

As we, the robb'd, leave rage, and pity it.

At first he made low shifts, would pick and glean,

Buy the reversion of old plays ; now

grown

To a little wealth, and credit in the scene,

He takes up all, makes each man's wit his own :

And, told of this, he slights it. Tut, such crimes

The sluggish gaping auditor devours ;

He marks not whose 'twas first : and after-times

May judge it to be his, as well as ours.

Fool ! as if half eyes will not know a fleece

From locks of wool, or shreds from the whole

piece ?

**********************************

The Returne from Parnassus

Ingenioso : (groaning, aside) It will be my luck to die no

other death than by hearing of his follies. I fear this speech

that's a-coming will breed a deadly DISEASE in my ears.

Gullio (beaming) Pardon fair lady,

though sick- thoughted Gullio makes amain unto thee, and

like a bold-faced suitor 'gins to woo thee!

Ingenioso :(puking) We shall have nothing but pure

Shakspeare, and shreds of poetry that he hath gathered at

the theatres.

other death than by hearing of his follies. I fear this speech

that's a-coming will breed a deadly DISEASE in my ears.

Gullio (beaming) Pardon fair lady,

though sick- thoughted Gullio makes amain unto thee, and

like a bold-faced suitor 'gins to woo thee!

Ingenioso :(puking) We shall have nothing but pure

Shakspeare, and shreds of poetry that he hath gathered at

the theatres.

***********************************

A fashionable disease - If thou couldst, doctor, cast. The water of my land, find her disease,. And purge it -

Sweet Swan of Avon! what a sight it were

To see thee in our WATERS yet appear,***********************************

Sexual Types: Embodiment, Agency, and Dramatic Character

from Shakespeare to Shirley

By Mario DiGangi

“In the dedication to the court that he included in the

Folio version of Cynthia's Revels, Jonson articulates through the conventional

image of the fountain the ideal correspondence between the virtuous courtier

and the virtuous court:

Thou are a bountiful and brave spring: and waterest all the

noble plants of this island. In thee, the whole kingdom dresseth itself, and is

abitious to use thee as her glass. Beware, then, thou render men’s figures

truly, and teach them no less to hate their deformities than to love their

forms: for, to grace there should come reverence; and no man can call that

lovely which is not also venerable. It is not powdering, perfuming, and every

day smelling of the tailor that converteth to a beautiful object: but a mind,

shining through any suit, which needs no false light either of riches, or

honours to help it. (Dedication 1-10) At once a “bountiful and brave spring”

for the nobility and a “glass” for the kingdom, the court should present only

truly virtuous “figures” as models of behaviour. The true courtier appears

“lovely” not because of a rich “suit” but because of the virtuous mind that

shines through his graceful “form.” By contrast, those courtiers obsessed with

powdering and perfuming are “deformities,” their riches and titles comparable

to the “false light” a merchant uses to mask defective goods. To avoid becoming

a “Spring of Self-love,” the court must reject such deformities (Dedication

13).

The difficulty with this imperative, as Mercury recognizes,

is in making apparent to all observers the difference between those courtiers

who do and those who do not “represent” the fountain of virtue at the center of

the kingdom. Mercury reassured Crites that when the unworthy courtiers are

finally exposed and humiliated, those courtiers who know themselves to be

virtuous will find their merit affirmed by this spectacle of punishment:

The better race in Court

That have the true nobility, called virtue,

Will apprehend it as a grateful right

Done to their separate merit: and approve

The fit rebuke of so ridiculous heads,

Thos with their apish customs and forced garbs

Would bring the name of courtier in contempt,

Did it not live unblemished in some few

Whom equal Jove hath loved, and Phoebus formed

Of better metal, and in better mould. (5.1.30-39)

*******************************************

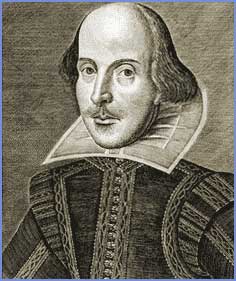

Droeshout as the Sign of the Unexemplary Courtier

The above passage (from DiGangi) contains a solution

to the mystery of the strange construction of the Droeshout engraving. The

Droeshout is a ‘spectacle of punishment’ – and a terrible brand at the front of

Shakespeare’s First Folio – a figure formed not of ‘better metal, and in better

mould’ but of 'worser' metal (brass) and 'worser' mould – in Jonson's opinion a fit rebuke of the

‘ridiculous’ heads that Jonson had attacked in Cynthia’s Revels. Shakespeare/Oxford,

the darling of aristocratic court society and the City gallants, was branded as base and vicious, and therefore ‘nothing worth’.

(Hamlet's 'Drossy Age'): drossy: i.e., worthless, frivolous. —In metallurgy, dross is the scum that forms on the surface of molten metal. )

Compare to Jonson's 1611 'Ignorant Age' dedication to the exemplary William Herbert:

(Hamlet's 'Drossy Age'): drossy: i.e., worthless, frivolous. —In metallurgy, dross is the scum that forms on the surface of molten metal. )

Compare to Jonson's 1611 'Ignorant Age' dedication to the exemplary William Herbert:

In so thick and dark an IGNORANCE, as now almost covers the AGE, I

crave leave to stand near your Light, and by that to be read. Posterity

may pay your Benefit the Honour and Thanks, when it shall know, that you

dare, in these Jig-given times, to countenance a Legitimate Poem. I

must call it so, against all noise of Opinion: from whose crude and airy

Reports, I appeal to that great and singular Faculty of Judgment in

your Lordship, able to vindicate Truth from Error.

*****************************************

Upon Ben: Johnson, the most excellent of Comick Poets.

Mirror of Poets! Mirror of our Age!

Which her whole Face beholding on thy stage,

Pleas'd and displeas'd with her owne faults endures,

A remedy, like Those whom Musicke cures,

Thou not alone those various inclinations,

Which Nature gives to Ages, Sexes, Nations,

Hast traced with thy All-resembling Pen,

But all that custome hath impos'd on Men,

Or ill-got Habits, which distort them so,

That scarce the Brother can the Brother know,

Is represented to the wondring Eyes,

Of all that see or read thy Comedies.

Whoever in those Glasses lookes may finde,

The spots return'd, or graces of his minde;

And by the helpe of so divine an Art,

At leisure view, and dresse his nobler part.

NARCISSUS conzen'd by that flattering Well,

Which nothing could but of his beauty tell,

Had here discovering the DEFORM'D estate

Of his fond minde, preserv'd himselfe with hate,

But Vertue too, as well as Vice is clad,

In flesh and blood so well, that Plato had

Beheld what his high Fancie once embrac'd,

Vertue with colour, speech and motion grac'd.

The sundry Postures of Thy copious Muse,

Who would expresse a thousand tongues must use,

Whose Fates no lesse peculiar then thy Art,

For as thou couldst all characters impart,

So none can render thine, who still escapes,

Like Proteus in variety of shapes,

Who was nor this nor that, but all we finde,

And all we can imagine in mankind.

E. Waller

Mirror of Poets! Mirror of our Age!

Which her whole Face beholding on thy stage,

Pleas'd and displeas'd with her owne faults endures,

A remedy, like Those whom Musicke cures,

Thou not alone those various inclinations,

Which Nature gives to Ages, Sexes, Nations,

Hast traced with thy All-resembling Pen,

But all that custome hath impos'd on Men,

Or ill-got Habits, which distort them so,

That scarce the Brother can the Brother know,

Is represented to the wondring Eyes,

Of all that see or read thy Comedies.

Whoever in those Glasses lookes may finde,

The spots return'd, or graces of his minde;

And by the helpe of so divine an Art,

At leisure view, and dresse his nobler part.

NARCISSUS conzen'd by that flattering Well,

Which nothing could but of his beauty tell,

Had here discovering the DEFORM'D estate

Of his fond minde, preserv'd himselfe with hate,

But Vertue too, as well as Vice is clad,

In flesh and blood so well, that Plato had

Beheld what his high Fancie once embrac'd,

Vertue with colour, speech and motion grac'd.

The sundry Postures of Thy copious Muse,

Who would expresse a thousand tongues must use,

Whose Fates no lesse peculiar then thy Art,

For as thou couldst all characters impart,

So none can render thine, who still escapes,

Like Proteus in variety of shapes,

Who was nor this nor that, but all we finde,

And all we can imagine in mankind.

E. Waller

*****************************************

An Art that showes th' Idea of his mind -- John Davies, Orchestra

*****************************************

Brass/Base Metal

An Unexemplary Metal, and Worse Figure:

Jonson, To the Reader (Shakespeare's First Folio)

This figure that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut,

Wherein the graver had a strife

With Nature, to out-do the life:

O could he but have drawn his wit

As well in brass, as he has hit

His face; the print would then surpass

All that was ever writ in brass:

But since he cannot, reader, look

Not on his picture, but his book.

This figure that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut,

Wherein the graver had a strife

With Nature, to out-do the life:

O could he but have drawn his wit

As well in brass, as he has hit

His face; the print would then surpass

All that was ever writ in brass:

But since he cannot, reader, look

Not on his picture, but his book.

( I may no longer on these PICTURES stay,--Jonson)

*****************************************

‘Master of Courtship’ Edward De Vere - Intro, Castiglione's Courtier:

For what more difficult, more noble, or more magnificent task has anyone ever undertaken than our author Castiglione, who has drawn for us the FIGURE and MODEL of a courtier, a work to which nothing can be added, in which there is no redundant word, a portrait which we shall recognize as that of a highest and most perfect type of man. And so, although NATURE herself has made nothing perfect in every detail, yet THE MANNERS OF MEN exceed in dignity that with which NATURE has endowed them; and he who SURPASSES others has here SURPASSED himself and has even OUT-DONE nature, which by no one has ever been SURPASSED.

For what more difficult, more noble, or more magnificent task has anyone ever undertaken than our author Castiglione, who has drawn for us the FIGURE and MODEL of a courtier, a work to which nothing can be added, in which there is no redundant word, a portrait which we shall recognize as that of a highest and most perfect type of man. And so, although NATURE herself has made nothing perfect in every detail, yet THE MANNERS OF MEN exceed in dignity that with which NATURE has endowed them; and he who SURPASSES others has here SURPASSED himself and has even OUT-DONE nature, which by no one has ever been SURPASSED.

*****************************************

Conforming to God’s High Figures in Cynthia’s Revels:

Cynthia's Revels, Jonson

MERCURY. Why, Crites, think you any noble spirit,

Or any, worth the title of a man,

Will be incensed to see the enchanted veils

Of self-conceit, and servile flattery,

Wrapt in so many folds by time and custom,

Drawn from his wronged and bewitched eyes?

Who sees not now their shape and nakedness, Is blinder than the son of earth, the mole;

Crown'd with no more humanity, nor soul.

CRITES. Though they may see it, yet the huge estate

FANCY, and FORM, and SENSUAL PRIDE have gotten,

Will make them blush for anger, not for shame,

And turn shewn nakedness to impudence.

Humour is now the test we try things in:

All power is just: nought that delights is sin.

And yet the zeal of every knowing man

Opprest with hills of tyranny, cast on virtue

By the light fancies of fools, thus transported.

Cannot but vent the Aetna of his fires,

T'inflame best bosoms with much worthier love

Than of these outward and effeminate shades;

That these vain joys, in which their WILLS consume

Such powers of wit and soul as are of force

To raise their beings to eternity,

May be converted on works fitting men:

And, for the practice of a forced look,

An antic gesture, or a fustian phrase,

Study the native frame of a true heart,

An inward comeliness of bounty, knowledge,

And spirit that may conform them actually

To God's HIGH FIGURES, which they have in power;

Which to neglect for a self-loving neatness,

Is sacrilege of an unpardon'd greatness.

MER. Then let the truth of these things strengthen thee,

In thy exempt and only man-like course;

Like it the more, the less it is respected:

Though men fail, virtue is by gods protected. --

See, here comes Arete; I'll withdraw myself. [EXIT.]

***********************************

Shake-speare, great heir of aristocratic extravagance, and

the darling of the Tempestuous Grandlings/Greeklings of the Elizabethan and Jacobean

courts. Jonson would attack these silken men in his ‘loathsome Age’ speech (after the rejection of his 'New Inn'), ridiculing the barbarous tastes of the ‘play-club’. A more detailed critique of

the undesirable social forms of the ancient nobility emerges in Jonson’s ‘Speech According to Horace’ – a group

that brazenly proved resistant to the exemplary forms of Jonson’s art.

***********************************

A Speech according to Horace. --Jonson

(snip)

And could (if our great Men would let their Sons

Come to their Schools,) show 'em the use of Guns.

And there instruct the noble English Heirs

In Politick, and Militar Affairs;

But he that should perswade, to have this done

For Education of our Lordings; Soon

Should he hear of Billow, Wind, and Storm,

From the Tempestuous Grandlings, who'll inform

Us, in our bearing, that are thus, and thus,

Born, bred, allied? what's he dare tutor us?

Are we by Book-worms to be aw'd? must we

Live by their Scale, that dare do nothing free?

Why are we Rich, or Great, except to show

All licence in our Lives? What need we know?

More then to praise a Dog? or Horse? or speak

The Hawking Language? or our Day to break

With Citizens? let Clowns, and Tradesmen breed

Their Sons to study Arts, the Laws, the Creed:

We will believe like Men of our own Rank,

In so much Land a year, or such a Bank,

That turns us so much Monies, at which rate

Our Ancestors impos'd on Prince and State.

Let poor Nobility be vertuous: We,

Descended in a Rope of Titles, be

From Guy, or Bevis, Arthur, or from whom

The Herald will. Our Blood is now become,

Past any need of Vertue. Let them care,

That in the Cradle of their Gentry are;

To serve the State by Councels, and by Arms:

We neither love the Troubles, nor the harms.

What love you then? your Whore? what study? Gate,

Carriage, and Dressing. There is up of late

The ACADEMY, where the Gallants meet ——

What to make Legs? yes, and to smell most sweet,

All that they do at Plays. O, but first here

They learn and study; and then practise there.

But why are all these Irons i' the Fire

Of several makings? helps, helps, t' attire

His Lordship. That is for his Band, his Hair

This, and that Box his Beauty to repair;

This other for his Eye-brows; hence, away,

I may no longer on these PICTURES stay,

These Carkasses of Honour; Taylors blocks,

Cover'd with Tissue, whose prosperity mocks

The fate of things: whilst totter'd Vertue holds

Her broken Arms up, to their EMPTY MOULDS.

(snip)

And could (if our great Men would let their Sons

Come to their Schools,) show 'em the use of Guns.

And there instruct the noble English Heirs

In Politick, and Militar Affairs;

But he that should perswade, to have this done

For Education of our Lordings; Soon

Should he hear of Billow, Wind, and Storm,

From the Tempestuous Grandlings, who'll inform

Us, in our bearing, that are thus, and thus,

Born, bred, allied? what's he dare tutor us?

Are we by Book-worms to be aw'd? must we

Live by their Scale, that dare do nothing free?

Why are we Rich, or Great, except to show

All licence in our Lives? What need we know?

More then to praise a Dog? or Horse? or speak

The Hawking Language? or our Day to break

With Citizens? let Clowns, and Tradesmen breed

Their Sons to study Arts, the Laws, the Creed:

We will believe like Men of our own Rank,

In so much Land a year, or such a Bank,

That turns us so much Monies, at which rate

Our Ancestors impos'd on Prince and State.

Let poor Nobility be vertuous: We,

Descended in a Rope of Titles, be

From Guy, or Bevis, Arthur, or from whom

The Herald will. Our Blood is now become,

Past any need of Vertue. Let them care,

That in the Cradle of their Gentry are;

To serve the State by Councels, and by Arms:

We neither love the Troubles, nor the harms.

What love you then? your Whore? what study? Gate,

Carriage, and Dressing. There is up of late

The ACADEMY, where the Gallants meet ——

What to make Legs? yes, and to smell most sweet,

All that they do at Plays. O, but first here

They learn and study; and then practise there.

But why are all these Irons i' the Fire

Of several makings? helps, helps, t' attire

His Lordship. That is for his Band, his Hair

This, and that Box his Beauty to repair;

This other for his Eye-brows; hence, away,

I may no longer on these PICTURES stay,

These Carkasses of Honour; Taylors blocks,

Cover'd with Tissue, whose prosperity mocks

The fate of things: whilst totter'd Vertue holds

Her broken Arms up, to their EMPTY MOULDS.

****************************************

Tempestuous Grandlings/Graeculi

There is up of late

The ACADEMY, where the Gallants meet ——

What to make Legs? yes, and to smell most sweet,

All that they do at Plays.

William Jaggard: Cupid's

Cabinet Unlocked, Or, The New Accademy of Complements by W. Shakespeare

The title-page of this undated duodecimo volume does not indicate when or by whom it was printed, but describes it as 'Cupids Cabinet unlock't, Or, THE NEW ACCADEMY OF COMPLEMENTS. Odes, Epigrams, Songs, and Sonnets, Poesies, Presentations, Congratulations, Ejaculatins, Rhapsodies, &c.' writeen 'By W. Shakespeare'. Bound with the Art of Courtship

The title-page of this undated duodecimo volume does not indicate when or by whom it was printed, but describes it as 'Cupids Cabinet unlock't, Or, THE NEW ACCADEMY OF COMPLEMENTS. Odes, Epigrams, Songs, and Sonnets, Poesies, Presentations, Congratulations, Ejaculatins, Rhapsodies, &c.' writeen 'By W. Shakespeare'. Bound with the Art of Courtship

***************************************

More 'ridiculous heads':

Hamlet's Drossy Age: More 'ridiculous heads':

Chapman, Revenge of Bussy D'Ambois

Clermont:

They are the breathing sepulchres of noblesse:

No trulier noble men, then lions pictures

Hung up for signs are lions. (2.1. l.154-156)

(snip)

A man may well

compare them to those foolish great-spleened camels

That, to their high heads, begged of Jove horns higher;

Whose most uncomely and ridiculous pride

When he had satisfied, they could not use,

But where they went upright before, they stooped,

And bore their heads much lower for their horns;

As these high men do, low in all true grace,

Their height being privilege to all things base.

And as the foolish poet that still writ

All his most self-loved verse in paper royal

Or parchment ruled with lead, smoothed with the pumice,

Bound richly up, and strung with crimson strings;

Never so blest as when he writ and read

The ape-loved issue of his brain, and never

But joying in himself, ADMIRING EVER,

Yet in his works behold him, and he showed

Like to a ditcher: so these painted men

All set on outside, look upon within

And not a peasants entrails you shall find

More foul and measled, nor more starved of mind.

Clermont:

They are the breathing sepulchres of noblesse:

No trulier noble men, then lions pictures

Hung up for signs are lions. (2.1. l.154-156)

(snip)

A man may well

compare them to those foolish great-spleened camels

That, to their high heads, begged of Jove horns higher;

Whose most uncomely and ridiculous pride

When he had satisfied, they could not use,

But where they went upright before, they stooped,

And bore their heads much lower for their horns;

As these high men do, low in all true grace,

Their height being privilege to all things base.

And as the foolish poet that still writ

All his most self-loved verse in paper royal

Or parchment ruled with lead, smoothed with the pumice,

Bound richly up, and strung with crimson strings;

Never so blest as when he writ and read

The ape-loved issue of his brain, and never

But joying in himself, ADMIRING EVER,

Yet in his works behold him, and he showed

Like to a ditcher: so these painted men

All set on outside, look upon within

And not a peasants entrails you shall find

More foul and measled, nor more starved of mind.

************************************

drossy: i.e., worthless, frivolous. —In metallurgy, dross is the scum that forms on the surface of molten metal.

Hamlet - Prince's mind imbued with Humanist and militant Protestant pedagogy. Rejects the aristocratic model of courtship as effeminate and worthless and seeks to model himself after heroic exemplars (Brutus/Aeneas). Unfortunately the violence inherent in heroic and militant rhetoric (ambiguous armed figures) wreak havoc in the Danish court. Imitates Brutus' feigned madness. Comedy is satirical (Jonsonian) rather than festive.

Hamlet - Heterosocial courtier Oxford/Shakespeare's response to Cynthia's Revels? Hamlet and Horatio/Horace most resemble Jonson's Crites/Criticus in CR. Hamlet's tastes and opinions appear to be modelled after those of Ben Jonson. Homosocial. Commentary on Jonson's 'consociation' of Prince and Poet? Ambitious 'Roman' Horatio/Horace quickly establishes himself as the foremost scholar/poet of the Norwegian Prince Fortinbras' court. (Mixed allegiances of continental humanism?)

*****************************************

Male impersonators: men performing masculinity

By Mark Simpson

According to the Greek myth Narcissus was told by the blind seer Teiresias when he was a child that he should live to a great age if he never knew himself. Narcissus grew up to be a beautiful young man but proud and haughty. An embittered youth, unrequited in his love for Narcissus, cursed him to love that which could not be obtained. One day on Mount Helicon Narcissus caught sight of his own reflection 'endowed with all the beauty that man could desire and unawares he began to love the image of himself which, although itself perfect beauty, could not return his love.' Narcissus, worn out by the futility of his love, turned into the yellow-centred flower with white petals named after him.

The myth tells us something about the relation of modern man to his own image. Narcissus is not seduced by his reflection in any common pool - he glimpses and falls in love with his reflection on Mount Helicon, the sacred mountain where Apollo, Artemis and the Muses danced: the symbolic centre of the arts. His reflection is not one of nature but an idealized image refracted through man's art. Thus his image is 'endowed with all the beauty that man could desire' and he falls in love with it. And like nineties Western man, Narcissus finds that it is a love that 'could not be obtained'.

By Mark Simpson

According to the Greek myth Narcissus was told by the blind seer Teiresias when he was a child that he should live to a great age if he never knew himself. Narcissus grew up to be a beautiful young man but proud and haughty. An embittered youth, unrequited in his love for Narcissus, cursed him to love that which could not be obtained. One day on Mount Helicon Narcissus caught sight of his own reflection 'endowed with all the beauty that man could desire and unawares he began to love the image of himself which, although itself perfect beauty, could not return his love.' Narcissus, worn out by the futility of his love, turned into the yellow-centred flower with white petals named after him.

The myth tells us something about the relation of modern man to his own image. Narcissus is not seduced by his reflection in any common pool - he glimpses and falls in love with his reflection on Mount Helicon, the sacred mountain where Apollo, Artemis and the Muses danced: the symbolic centre of the arts. His reflection is not one of nature but an idealized image refracted through man's art. Thus his image is 'endowed with all the beauty that man could desire' and he falls in love with it. And like nineties Western man, Narcissus finds that it is a love that 'could not be obtained'.

************************************

**************************************

Shakespeare

SInne of ſelfe-loue poſſeſſeth al mine eie,

And all my ſoule,and al my euery part;

And for this ſinne there is no remedie,

It is ſo grounded inward in my heart.

Me thinkes no face ſo gratious is as mine,

No ſhape ſo true,no truth of ſuch account,

And for my ſelfe mine owne worth do define,

As I all other in all worths ſurmount.

But when my glaſſe ſhewes me my ſelfe indeed

Beated and chopt with tanned antiquitie,

Mine owne ſelfe loue quite contrary I read

Selfe,ſo ſelfe louing were iniquity,

T'is thee(my ſelfe)that for my ſelfe I praiſe,

Painting my age with beauty of thy daies,

***************************************

And though thou hadst small Latin and less Greek -- Jonson on Shakespeare

Spenser, Faerie Queene

To the right Honourable the Earle

of Oxenford, Lord high Chamberlayne of

England. &c.

To the right Honourable the Earle

of Oxenford, Lord high Chamberlayne of

England. &c.

And also for the LOVE, which thou doest beare

To th'HELICONIAN YMPS, and they to thee,

They vnto thee, and thou to them most deare:

DEARE as thou art UNTO THY SELFE, so LOVE

That LOVES & honours thee, *as doth behoue*.

To th'HELICONIAN YMPS, and they to thee,

They vnto thee, and thou to them most deare:

DEARE as thou art UNTO THY SELFE, so LOVE

That LOVES & honours thee, *as doth behoue*.

**************************************

Shakespeare

SInne of ſelfe-loue poſſeſſeth al mine eie,

And all my ſoule,and al my euery part;

And for this ſinne there is no remedie,

It is ſo grounded inward in my heart.

Me thinkes no face ſo gratious is as mine,

No ſhape ſo true,no truth of ſuch account,

And for my ſelfe mine owne worth do define,

As I all other in all worths ſurmount.

But when my glaſſe ſhewes me my ſelfe indeed

Beated and chopt with tanned antiquitie,

Mine owne ſelfe loue quite contrary I read

Selfe,ſo ſelfe louing were iniquity,

T'is thee(my ſelfe)that for my ſelfe I praiſe,

Painting my age with beauty of thy daies,

And though thou hadst small Latin and less Greek -- Jonson on Shakespeare

Alciato's Book of Emblems

Emblem 69

Self-love

Because your figure pleased you too much, Narcissus, it was changed into a flower, a plant of known senselessness. Self-love is the withering and destruction of natural power which brings and has brought ruin to many learned men, who having thrown away the METHOD OF THE ANCIENTS seek new doctrines and pass on nothing but their own fantasies.

Emblem 69

Self-love

Because your figure pleased you too much, Narcissus, it was changed into a flower, a plant of known senselessness. Self-love is the withering and destruction of natural power which brings and has brought ruin to many learned men, who having thrown away the METHOD OF THE ANCIENTS seek new doctrines and pass on nothing but their own fantasies.

Jonson’s Scope:

To draw no envy, SHAKSPEARE, on thy name,

Am I thus ample to thy book and fame ;

Am I thus ample to thy book and fame ;

************************************

Jonson, Cynthia's Revels

Cynthia: Dear Arete, and Crites, to you two

We give the Charge; impose what Pains you please:

TH' INCURABLE CUT OFF, the rest REFORM,

Remembring ever what we first decreed,

Since Revels were proclaim'd, let now none bleed.

Arete. How well Diana can distinguish Times,

And sort her Censures, keeping to her self

The Doom of Gods, leaving the rest to us?

Come, cite them, Crites, first, and then proceed.

(snip)

Then, Crites, practise thy DISCRETION.

Cynthia: Dear Arete, and Crites, to you two

We give the Charge; impose what Pains you please:

TH' INCURABLE CUT OFF, the rest REFORM,

Remembring ever what we first decreed,

Since Revels were proclaim'd, let now none bleed.

Arete. How well Diana can distinguish Times,

And sort her Censures, keeping to her self

The Doom of Gods, leaving the rest to us?

Come, cite them, Crites, first, and then proceed.

(snip)

Then, Crites, practise thy DISCRETION.

*****************************************

(The word [discretion] was almost invariably used in

Elizabethan England as a means of constructing social, cultural, or aesthetic

difference. (David Hillman, Puttenham, Shakespeare, and the abuse of

rhetoric).

*****************************************

Cartwright, William, Jonsonus Virbius

...Blest life of Authors, unto whom we owe

Those that we have, and those that we want too:

Th'art all so good, that reading makes thee worse,

And to have writ so well's thine onely curse.

Secure then of thy merit, thou didst hate

That servile base dependance upon fate:

Successe thou ne'r thoughtst vertue, nor that fit,

Which chance, and TH'AGES FASHION DID MAKE HIT;

Excluding those from life in after-time,

Who into Po'try first brought luck and rime:

Who thought the peoples breath good ayre: sty'ld name

What was but noise; and getting Briefes for fame

Gathered the many's suffrages, and thence

Made COMMENDATION a BENEVOLENCE:

THY thoughts were their owne Lawrell, and did win

That best applause of being crown'd within..

...Blest life of Authors, unto whom we owe

Those that we have, and those that we want too:

Th'art all so good, that reading makes thee worse,

And to have writ so well's thine onely curse.

Secure then of thy merit, thou didst hate

That servile base dependance upon fate:

Successe thou ne'r thoughtst vertue, nor that fit,

Which chance, and TH'AGES FASHION DID MAKE HIT;

Excluding those from life in after-time,

Who into Po'try first brought luck and rime:

Who thought the peoples breath good ayre: sty'ld name

What was but noise; and getting Briefes for fame

Gathered the many's suffrages, and thence

Made COMMENDATION a BENEVOLENCE:

THY thoughts were their owne Lawrell, and did win

That best applause of being crown'd within..

*************************************

styl'd NAME what was but NOISE; and getting Briefes for fame/ Gathered the man's suffrages - Cartwright to Jonson

************************************

styl'd NAME what was but NOISE; and getting Briefes for fame/ Gathered the man's suffrages - Cartwright to Jonson

Name/noise

And though thou hadst small Latin and less Greek,

From thence, to honour thee, I would not seek

For names; but call forth thund’ring Aeschylus,

Euripides, and Sophocles to us,

Paccuvius, Accius, him of Cordova dead

To life again, to hear thy buskin tread

And shake a stage; or when thy socks were on,

Leave thee alone, for the comparison

Of all that insolent Greece or haughty Rome

Sent forth; or since did from their ashes come.

************************************

The Pursuit of Fame

In her epistle to noble and worthy ladies, as in many of her epistles, Cavendish straightforwardly expresses her desire for fame. Cavendish states that she is not concerned that the best people like her writing, as long as a great many people do. She justifies this by linking fame to NOISE and noise to great numbers of people.(Jonson/Hamlet - judicious 'theatre of one'.)

Noise/Opinion: Jonson to William Herbert - 'Jiggy' Shakespeare as 'Soul of an Ignorant Age'.

In so thick and dark an IGNORANCE, as now almost covers the AGE, I crave leave to stand near your Light, and by that to be read. Posterity may pay your Benefit the Honour and Thanks, when it shall know, that you dare, in these Jig-given times, to countenance a Legitimate Poem. I must call it so, against all NOISE of OPINION: from whose crude and airy Reports, I appeal to that great and singular Faculty of Judgment in your Lordship, able to vindicate Truth from Error.

***************************************

Shakespeare and his ignorant admirers disrupted Jonson's economy of learned praise:

Men/Vir vs. Parasites:

The COMMENDATION of good things may fall within a

many, their approbation but in a few· for the most

COMMEND OUT OF AFFECTION, selfe tickling, an easinesse, or

imitation: but MEN iudge only out of *KNOWLEDGE*. That is the trying faculty.

-- Jonson

I remember, the Players have often mentioned it as an honour

to Shakespeare, that in his writing, (whatsoever he penn'd) hee never blotted

out line. My answer hath beene, would he had blotted a thousand. Which they

thought a MALEVOLENT speech. I had not told posterity this, but for their

IGNORANCE, who choose that circumstance to COMMEND their friend by, wherein he

most FAULTED... -- Jonson on Shakespeare

***********************************

Return from Parnassus:

************************************

Return from Parnassus:

Gullio And, for matters of wit, oft have I sonneted it in

the commendations of her squirrel. And, very lately (I

remember that time I had a musk jerkin, laid all with gold

lace, and the rest of my furniture answerable - pretty

sleighty apparel, stood me in not long past in two hundred

pounds) - the froward fates cut her monkey's thread

asunder, and I, in the abundance of poetry, bestowed an

epitaph upon the deceased little creature!

Ingenioso : (applauding politely) I'faith, an excellent wit,

that can poetize vpon such mean subjects. Every John

Dringle can make a book in the commendations of

Temperance, against the Seven Deadly Sins; but that's a rare

wit that can make something of nothing, that can make an

epigram of a mouse, and an epitaph on a monkey.

the commendations of her squirrel. And, very lately (I

remember that time I had a musk jerkin, laid all with gold

lace, and the rest of my furniture answerable - pretty

sleighty apparel, stood me in not long past in two hundred

pounds) - the froward fates cut her monkey's thread

asunder, and I, in the abundance of poetry, bestowed an

epitaph upon the deceased little creature!

Ingenioso : (applauding politely) I'faith, an excellent wit,

that can poetize vpon such mean subjects. Every John

Dringle can make a book in the commendations of

Temperance, against the Seven Deadly Sins; but that's a rare

wit that can make something of nothing, that can make an

epigram of a mouse, and an epitaph on a monkey.

From To the Deceased Author of these Poems (William

Cartwright)

by Jasper Mayne

...And as thy Wit was like a Spring, so all

The soft streams of it we may Chrystall call:

No cloud of Fancie, no mysterious stroke,

No Verse like those which antient Sybils spoke;

No Oracle of Language, to amaze

The Reader with a dark, or Midnight Phrase,

Stands in thy Writings, which are all pure Day,

A cleer, bright Sunchine, and the mist away.

That which Thou wrot'st was sense, and that sense good,

Things not first written, and then understood:

Or if sometimes thy Fancy soar'd so high

As to seem lost to the unlearned Eye,

'Twas but like generous Falcons, when high flown,

Which mount to make the Quarrey more their own.

For thou to Nature had'st joyn'd Art, and skill.

In Thee Ben Johnson still HELD SHAKESPEARE'S QUILL:

A QUILL, RUL'D by sharp Judgement, and such Laws,

As a well studied Mind, and Reason draws.

Thy Lamp was cherish'd with suppolied of Oyle,

Fetch'd from the Romane and the Graecian soyle. (snip)

by Jasper Mayne

...And as thy Wit was like a Spring, so all

The soft streams of it we may Chrystall call:

No cloud of Fancie, no mysterious stroke,

No Verse like those which antient Sybils spoke;

No Oracle of Language, to amaze

The Reader with a dark, or Midnight Phrase,

Stands in thy Writings, which are all pure Day,

A cleer, bright Sunchine, and the mist away.

That which Thou wrot'st was sense, and that sense good,

Things not first written, and then understood:

Or if sometimes thy Fancy soar'd so high

As to seem lost to the unlearned Eye,

'Twas but like generous Falcons, when high flown,

Which mount to make the Quarrey more their own.

For thou to Nature had'st joyn'd Art, and skill.

In Thee Ben Johnson still HELD SHAKESPEARE'S QUILL:

A QUILL, RUL'D by sharp Judgement, and such Laws,

As a well studied Mind, and Reason draws.

Thy Lamp was cherish'd with suppolied of Oyle,

Fetch'd from the Romane and the Graecian soyle. (snip)

**************************************

I over-tooke, comming from Italie,

In Germanie a great and famous Earle85

Of England, the most goodly fashion'd man

I ever saw; from head to foote in forme

Rare and most absolute; hee had a face

Like one of the most ancient honour'd Romanes

From whence his noblest familie was deriv'd;90

He was beside of spirit passing great,

Valiant, and learn'd, and liberall as the sunne,

Spoke and writ sweetly, or of learned subjects,

Or of the discipline of publike weales;

And t'was the Earle of Oxford: and being offer'd95

At that time, by Duke Cassimere, the view

Of his right royall armie then in field,

Refus'd it, and no foote was mov'd to stirre

Out of his owne free fore-determin'd course.

I, wondring at it, askt for it his reason,100

It being an offer so much for his honour.

Hee, all acknowledging, said t'was not fit

To take those honours that one cannot quit. (Revenge, III, iv, lines 84-104)

Of England, the most goodly fashion'd man

I ever saw; from head to foote in forme

Rare and most absolute; hee had a face

Like one of the most ancient honour'd Romanes

From whence his noblest familie was deriv'd;90

He was beside of spirit passing great,

Valiant, and learn'd, and liberall as the sunne,

Spoke and writ sweetly, or of learned subjects,

Or of the discipline of publike weales;

And t'was the Earle of Oxford: and being offer'd95

At that time, by Duke Cassimere, the view

Of his right royall armie then in field,

Refus'd it, and no foote was mov'd to stirre

Out of his owne free fore-determin'd course.

I, wondring at it, askt for it his reason,100

It being an offer so much for his honour.

Hee, all acknowledging, said t'was not fit

To take those honours that one cannot quit. (Revenge, III, iv, lines 84-104)

Ren. Twas answer'd like the man you have describ'd.

Clermont. AND YET he cast it onely in the way,105

To stay and serve the world. Nor did it fit

His owne true estimate how much it waigh'd;

FOR HEE DESPIS'D IT, and esteem'd it freer

To keepe his owne way straight, and swore that hee

Had rather make away his whole estate110

In things that crost the vulgar then he would

Be frozen up stiffe (like a Sir John Smith,

His countrey-man) in common Nobles fashions;

Affecting, as't the end of noblesse were,

Those servile observations.

Ren. It was strange. 115

Clermont. O tis a vexing sight to see a man,

OUT OF HIS WAY, stalke PROUD as HEE WERE IN;

OUT OF HIS WAY, to be officious,

Observant, wary, serious, and grave,

Fearefull, and passionate, insulting, raging,120

Labour with iron flailes to thresh downe feathers

Flitting in ayre.

Clermont. AND YET he cast it onely in the way,105

To stay and serve the world. Nor did it fit

His owne true estimate how much it waigh'd;

FOR HEE DESPIS'D IT, and esteem'd it freer

To keepe his owne way straight, and swore that hee

Had rather make away his whole estate110

In things that crost the vulgar then he would

Be frozen up stiffe (like a Sir John Smith,

His countrey-man) in common Nobles fashions;

Affecting, as't the end of noblesse were,

Those servile observations.

Ren. It was strange. 115

Clermont. O tis a vexing sight to see a man,

OUT OF HIS WAY, stalke PROUD as HEE WERE IN;

OUT OF HIS WAY, to be officious,

Observant, wary, serious, and grave,

Fearefull, and passionate, insulting, raging,120

Labour with iron flailes to thresh downe feathers

Flitting in ayre.

Oxfordian 'Invention' and Humanist 'Imitation':

Belles Lettres and Metropolitan Conversation:

...The problem of becoming genteel was that acquiring manners did not of itself give rise to taste. Tasteless persons could always mimic the dress and gestures of gentlepersons. These mock wits and would-be belles were the favorite butts of stage comedy...If taste could not be had by imitation, how was it acquired? Most readily by participating in the conversation of persons with taste until one had entered into the sensus communis of their expression. This did not mean gathering knowledge by precept. Rather, sensitivity to beauty and pleasure had to be heightened. An apperception of one's sensitivity made taste "conscious." The consciousness of taste endowed was not self-consciousness. Taste put one into accord with a style of expression. Beauty, if it were true beauty, for instance, was not personal; it was "natural" or "Attic" or "divine".

**********************************

Divine Oxford - Attici:

Nicholas Hilliard's Portrait of an Unknown Man Clasping a Hand from a Cloud is much smaller than you see it here. (Unlike most pictures, miniatures generally get enlarged in reproduction). In reality its dimensions are six by five centimetres. This image, in other words, is like a lock of hair in a locket. It's an image to be hung round the neck (rather than on the wall), worn close to the body, near to the heart. And it must be some kind of love token. Though the man is unidentified, and the inscription is obscure - "Attici amoris ergo" - it has love as its middle word, and it seems to be a lady's hand that descends from the cloud to hold the gentleman's.

****************************************

*****************************************

English Ciceronianism/Empty Formalism - words over matter (English Seneca - What is the matter?)

*****************************************

I have seen many Latin verses of thine, yea,

even more English verses are extant;

thou hast drunk deep draughts not only of the Muses of France and Italy,

but hast learned the manners of many men, and the arts of foreign countries.

It was not for nothing that STURMIUS , himself was visited by thee;

neither in France, Italy, nor Germany are any such cultivated and polished men.

******************************************

An Art that showes th' IDEA of his mind -- John Davies, Orchestra

*******************************************

"Science and the Secrets of Nature"

by William Eamon

The distinguishing mark of the courtier, according to

Castiglione, was grazia, or grace, "a seasoning without which all the

other properties and good qualities would be of little worth."

Essentially identical with elegance, urbanity, and refinement, grace was

the highest achievement of culture. Grazia may be displayed in any

action, but the key to it was an art for which Castiglione coined the term

sprezzatura, a kind of smoothness and nonchalance that hides the effort that

goes into a difficult performance. However, "nonchalance"

conveys only part of the meaning of sprezzatura. The root of this

untranslatable word is the verb sprezzare, meaning to SCORN or despise.

Chen Castiglione demands that the courtier act with "una certa

sprezzatura" toward what is unimportant, he implies acting with an

attitude of disdain and scorn for normal human limitations or physical

necessities. Castiglione put it down as a "universal rule" of

courtly behavior that to achieve gracefulness one must "practice in all

things a certain sprezzatura, so as to conceal all art and make whatever is

done or said appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about

it." The more difficult the performance, the greater the possibility

of manifesting sprezzatura, the art that makes what is difficult seem simple

and natural. This is why, when a courtier accomplishes an action with

sprezzatura, his behavior elicits another characteristic courtly response,

meraviglia, or wonder: "because everyone knows the difficulty of things

that are rare and well done; wherefore facility in such things causes the

greatest wonder."

Courtly virtuosity, with its feigned disregard for normal

limitations and the high esteem it attached to wonderment, fostered - indeed

idealized - a dilettantish approach to intellectual and cultural pursuits. The

accomplished courtier did not pursue learning with the diligence of a scholar,

nor play the lute like a professional, nor fight like a condottiere. He

performed everything with sprezzatura, which made his actions appear as a

pastime, success as a matter of course. *Feigning his accomplishments as

natural* made the courtier seem to to be the master of himself, of society's

rules, and even of physical laws. Holding himself above the common crowd,

disdaining the obvious and merely useful, he turned his curiosity toward what

was obscure, rare, and "marvelous."

************************************

Gabriel Harvey, Rhetor

On Art.

Can anyone be an artist without art? Or have you ever seen a bird flying without wings, or a horse running without feet? Or if you have seen such things, which no one else has ever seen, come, tell me please, do you hope to become a goldsmith, or a painter, or a sculptor, or a musician, or an architect, or a weaver, or any sort of artist at all without a teacher? But how much easier are all these things, than that you develop into a supreme and perfect orator without the art of public speaking. There is need of a teacher, and indeed even an excellent teacher, who might point out the springs with his finger, as it were, and carefully pass on to you the art of speaking colorfully, brilliantly, copiously. But what sort of art shall we choose? Not an art entangled in countless difficulties, or packed with meaningless arguments; not one sullied by useless [31] precepts, or disfigured by strange and foreign ones; not an art polluted by any filth, or fashioned to accord with our own will and judgment; not a single art joined and sewn together from many, like a quilt from many rags and skins (way too many rhetoricians have given this sort of art to us, if indeed one may call art that which conforms to no artistic principles). We want rather an art that is concise, precise, appropriate, lucid, accessible; one that is decorated and illuminated by precise definitions, accurate divisions, and striking illustrations, as if by flashing gems and stars; one that emerges, and in a way bursts into flower, from the speech of the most eloquent men and the best orators. Why so? Not only because brevity is pleasant, and clarity delightful, but also so that eloquence might be learned in a shorter time, and with less labor and richer results, and so that it might stand more firmly grounded, secured by deeper roots. For thus said the gifted poet in his Ars Poetica: "Whatever instruction you give, let it be brief." Why? [32] He gives two reasons: "So that receptive minds might swiftly grasp your words and accurately retain them." And indeed, as the same poet elegantly adds: "Everything superfluous spills from a mind that's full."

(snip)

But those annual whistles and shouts I hear indicate that almost all, or at least the greater part of my auditors are newcomers, who do not understand what they should do or whom they should imitate, but who nonetheless are captivated by the splendor of rhetoric, and seek to be orators. Therefore I will now, if I am able, reveal those things and place them all in their view, in such a way that they might seem to see them with their eyes, and almost hold them in their hands. In the meantime I pray you, most eloquent and refined gentlemen, either withdraw, if you like, or with the kindness that you've shown so far hear me as I recite some precepts so common as to be almost elementary. And from those whose tongues and ears Cicero alone inhabits, I beg forgiveness, if by chance I let drop in my haste a word that is un-Ciceronian. We cannot all be Longeuils and Cortesis: [9] some of us don't want to be. As for those who study more Latin authors, but only the best and choicest, and who to accompany Cicero, the foremost of all, add Caesar, Varro, Sallust, Livy, Seneca, Terence too, and Plautus and Vergil and Horace, I am sure they will be sympathetic to me. For reading as I do many works by many authors, sometimes even the poets, as Crassus bids in Cicero, I cannot guarantee that in so impromptu an oration I will not use a word not found in a Ciceronian phrase book.

But those little CROWS and APES of Cicero were long ago driven from the stage by the hissing and laughter of the learned, as they so well deserved, and at last have almost vanished; and I now hope to find not only eager and attentive auditors, but friendly spectators as well, not the sort who scrupulously weigh every individual detail on the scales of their own refined tastes, but who interpret everything in a fair and good-natured way. I too in fact wanted, if I was able--but perhaps I was not--to speak in as Ciceronian a style as the Ciceronianest of them all. [10] Forgive me, illustrious Ciceronians, if I ought not use that word in the superlative.

On Art.

Can anyone be an artist without art? Or have you ever seen a bird flying without wings, or a horse running without feet? Or if you have seen such things, which no one else has ever seen, come, tell me please, do you hope to become a goldsmith, or a painter, or a sculptor, or a musician, or an architect, or a weaver, or any sort of artist at all without a teacher? But how much easier are all these things, than that you develop into a supreme and perfect orator without the art of public speaking. There is need of a teacher, and indeed even an excellent teacher, who might point out the springs with his finger, as it were, and carefully pass on to you the art of speaking colorfully, brilliantly, copiously. But what sort of art shall we choose? Not an art entangled in countless difficulties, or packed with meaningless arguments; not one sullied by useless [31] precepts, or disfigured by strange and foreign ones; not an art polluted by any filth, or fashioned to accord with our own will and judgment; not a single art joined and sewn together from many, like a quilt from many rags and skins (way too many rhetoricians have given this sort of art to us, if indeed one may call art that which conforms to no artistic principles). We want rather an art that is concise, precise, appropriate, lucid, accessible; one that is decorated and illuminated by precise definitions, accurate divisions, and striking illustrations, as if by flashing gems and stars; one that emerges, and in a way bursts into flower, from the speech of the most eloquent men and the best orators. Why so? Not only because brevity is pleasant, and clarity delightful, but also so that eloquence might be learned in a shorter time, and with less labor and richer results, and so that it might stand more firmly grounded, secured by deeper roots. For thus said the gifted poet in his Ars Poetica: "Whatever instruction you give, let it be brief." Why? [32] He gives two reasons: "So that receptive minds might swiftly grasp your words and accurately retain them." And indeed, as the same poet elegantly adds: "Everything superfluous spills from a mind that's full."

(snip)

But those annual whistles and shouts I hear indicate that almost all, or at least the greater part of my auditors are newcomers, who do not understand what they should do or whom they should imitate, but who nonetheless are captivated by the splendor of rhetoric, and seek to be orators. Therefore I will now, if I am able, reveal those things and place them all in their view, in such a way that they might seem to see them with their eyes, and almost hold them in their hands. In the meantime I pray you, most eloquent and refined gentlemen, either withdraw, if you like, or with the kindness that you've shown so far hear me as I recite some precepts so common as to be almost elementary. And from those whose tongues and ears Cicero alone inhabits, I beg forgiveness, if by chance I let drop in my haste a word that is un-Ciceronian. We cannot all be Longeuils and Cortesis: [9] some of us don't want to be. As for those who study more Latin authors, but only the best and choicest, and who to accompany Cicero, the foremost of all, add Caesar, Varro, Sallust, Livy, Seneca, Terence too, and Plautus and Vergil and Horace, I am sure they will be sympathetic to me. For reading as I do many works by many authors, sometimes even the poets, as Crassus bids in Cicero, I cannot guarantee that in so impromptu an oration I will not use a word not found in a Ciceronian phrase book.

But those little CROWS and APES of Cicero were long ago driven from the stage by the hissing and laughter of the learned, as they so well deserved, and at last have almost vanished; and I now hope to find not only eager and attentive auditors, but friendly spectators as well, not the sort who scrupulously weigh every individual detail on the scales of their own refined tastes, but who interpret everything in a fair and good-natured way. I too in fact wanted, if I was able--but perhaps I was not--to speak in as Ciceronian a style as the Ciceronianest of them all. [10] Forgive me, illustrious Ciceronians, if I ought not use that word in the superlative.

*************************************

Greene's Groatsworth:

With thee I ioyne yong Iuuenall, that byting Satyrist, that lastlie with mee together writ a Comedie. Sweete boy, might I aduise thee, be aduisde, and get not many enemies by bitter wordes: inueigh against vaine men, for thou canst do it, no man better, no man so wel: thou hast a libertie to reprooue all, and none more; for one being spoken to, all are offended, none being blamed no man is iniured. Stop shallow water still running, it will rage, or tread on a worme and it will turne: then blame not Schollers vexed with sharpe lines, if they reproue thy too much libertie of reproofe.

And thou no lesse deseruing than the other two, in some things rarer, in nothing inferiour; driuen (as my selfe) to extreme shifts, a little haue I to say to thee: and were it not an idolatrous oth, I would sweare by sweet S. George, thou art vnworthy better hap, sith thou dependest on so meane a stay. Base minded men all three of you, if by my miserie ye be not warned: for vnto none of you (like me) sought those burres to cleaue: those Puppets (I meane) that speake from our mouths, those Anticks garnisht in our colours. Is it not strange that I, to whom they al haue beene beholding: is it not like that you, to whome they all haue beene beholding, shall (were yee in that case that I am now) bee both at once of them forsaken? Yes, trust them not: for there is an vpstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Iohannes fac totum, is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrey. O that I might intreate your rare wits to be imploied in more profitable courses: & let those Apes imitate your past excellence, and neuer more acquaint them with your admired inuentions. I know the best husband of you all will neuer proue an Usurer, and the kindest of them all will neuer seeke you a kind nurse: yet whilest you may, seeke you better Maisters; for it is pittie men of such rare wits, should be subiect to the pleasure of such rude groomes.

In this I might insert two more, that both haue writ against these buckram Gentlemen: but let their owne works serue to witnesse against their owne wickednesse, if they perseuere to mainteine any more such peasants. For other new-commers, I leaue them to the mercie of these painted monsters, who (I doubt not) will driue the best minded to despise them: for the rest, it skils not though they make a ieast at them.

With thee I ioyne yong Iuuenall, that byting Satyrist, that lastlie with mee together writ a Comedie. Sweete boy, might I aduise thee, be aduisde, and get not many enemies by bitter wordes: inueigh against vaine men, for thou canst do it, no man better, no man so wel: thou hast a libertie to reprooue all, and none more; for one being spoken to, all are offended, none being blamed no man is iniured. Stop shallow water still running, it will rage, or tread on a worme and it will turne: then blame not Schollers vexed with sharpe lines, if they reproue thy too much libertie of reproofe.